Mophead

My oldest brother, Dylan, and I look somewhat alike. If you took a good look at us, you could tell we were siblings after around twenty seconds. Same glasses. Same nose. Same lips. But what happens if I decide to get the same hair as him? (I buzzed it all off two months later.)

We got home from the salon, and my parents flew down the stairs to get a good look at me. They stared in disbelief and touched my hair as if a bird pooped in it. But it was even worse.

My cousin Brian walked through the front door and stopped in his tracks. “Nice hair mopheads.”

My parents were still in a state of utter shock that I got a perm. It smelled like a donkey’s fart. Dylan’s had one for two years already, but now another child has one too?

Brian was my family’s favorite cousin. He always showed up to our house, though he mostly stole food out of the fridge. His opinion was highly valued by my siblings and me, but he’s a story for another time.

That night, my family had a dinner reservation with my mom’s cousins and close friends, but Dylan had planned a dinner with his girlfriend. As I got called down to head to dinner, I frantically ran to my closet to grab a hoodie to cover the top of my head. Looking in the mirror, I could see the curls on my forehead, but not the rest of the mop.

I ran downstairs, got in the car, and thought of every situation that could’ve happened when they saw me. I was expecting a couple of “oohs,” a couple of “ahhs,” and a couple of “ewwwws,” but I didn’t foresee this happening at all.

I stepped out of the car and greeted my Aunt Andrea with a side hug. “It’s so nice to see you again, Dylan!”

Dylan? Me? Dylan??? “Awww, thanks, Auntie. It’s so nice to see you too!”

To this day, I have no clue why I played along. But the rest of the relatives didn’t even second guess that I was Dylan. I almost went through the entire dinner without ANYONE noticing. Until my Uncle Adam, during dessert, asked across the table, “How’s volleyball going, Peanut Butter?”

I chuckled and looked around the table, knowing that that one question, confused everyone there. “It’s going good, I just got announced captain,” I responded, knowing that I had the

Same glasses. Same nose. Same lips. Same hair now too.

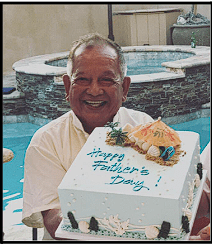

Yeye

Yeye

My yeye was the happiest person you could ever meet. Always smiling, singing, dancing with my mama, teaching my siblings and I new ways to roll an eggroll. Yeye is grandpa in Chinese, and mama means grandma. They were my dad’s parents and they taught me all of the manners I know today. Don’t chew with your mouth open, pick up your feet when you walk, say please, say thank you, and offer food or money to the homeless; all ways to make life better for all. But my grandparents were also the main reason I got chubby. As the youngest at the time, they never knew how to say no to me. My yeye would roll eggrolls and fry them if I said I was hungry, would give me seaweed and rice whenever I asked, taught me the best ratios for the best crunch, and they got me whatever fast food I was craving at the time (mainly Carl’s Jr.). He was the best. Was.

I was at my mom’s parents’ house at the time, my ba ngoai and ong ngoai. I was on the island table eating apples that my grandma had cut up when her phone rang. As she listened, I slowly saw her face go into distress. As an 8-year-old, I knew not to say anything and just continued doing what I was doing. I picked up my iPad and she snatched it out of my hand. “GET OFF NOW, YOUR YEYE JUST DIED AND YOU HAVE THE AUDACITY TO BE PLAYING GAMES? DID YOU EVEN KNOW THAT HE’S DEAD?” she screamed at me in Vietnamese.

The house went silent. My ong ngoai staring at me, my ba ngoai still clenching onto the iPad, and I was sitting at the island table in disbelief. I didn’t know what to do at that moment and didn’t know what to feel, so I asked for my iPad back so I could continue playing. I didn’t know any better. I knew that he was sick and was in the hospital, but I didn’t know that when I visited him in the hospital, it would be his last time seeing me.

My dad picked me up and the car ride home was absolute silence. I made sure not to breathe too loudly, sat straight up on my seat, iPad in my lap, and observed my dad through the rearview mirror. His expression was dim, with bags under his eyes. “Dad, is yeye really dead?” I asked in a sullen tone.

He chuckled lightly and said, “Yes con, he really is.” That was my first memory of my dad crying.

At the funeral, I was asked to sing our favorite song together. Tian Mi Mi, by Teresa Teng. My yeye sang it to me every bedtime and every car ride home from school. That was the last time I’ve ever cried. In front of my entire family, in front of the people in Holy Spirit Church, whilst singing our favorite song. When you’re eight years old, you don’t know what to expect in life. But I knew my yeye would be watching over me and protecting me from the evils for the rest of my life until it was time to join him once again.